Revisiting the newly restored classic film by William H. Whyte

In 2018, as we began to consider what we wanted to accomplish in the next chapter of our lives, we decided that one thing was to return to our roots, which began with William H. ("Holly") Whyte in the early 1970s, working on his Street Life Project. "The Social Life Project" name itself is, of course, an homage to his approach to studying how people actually use public spaces. Holly also created the roadmap for communicating the human factors that make successful public spaces, inspiring the way our articles are structured today with abundant people-centered photographs and simple key takeaways.

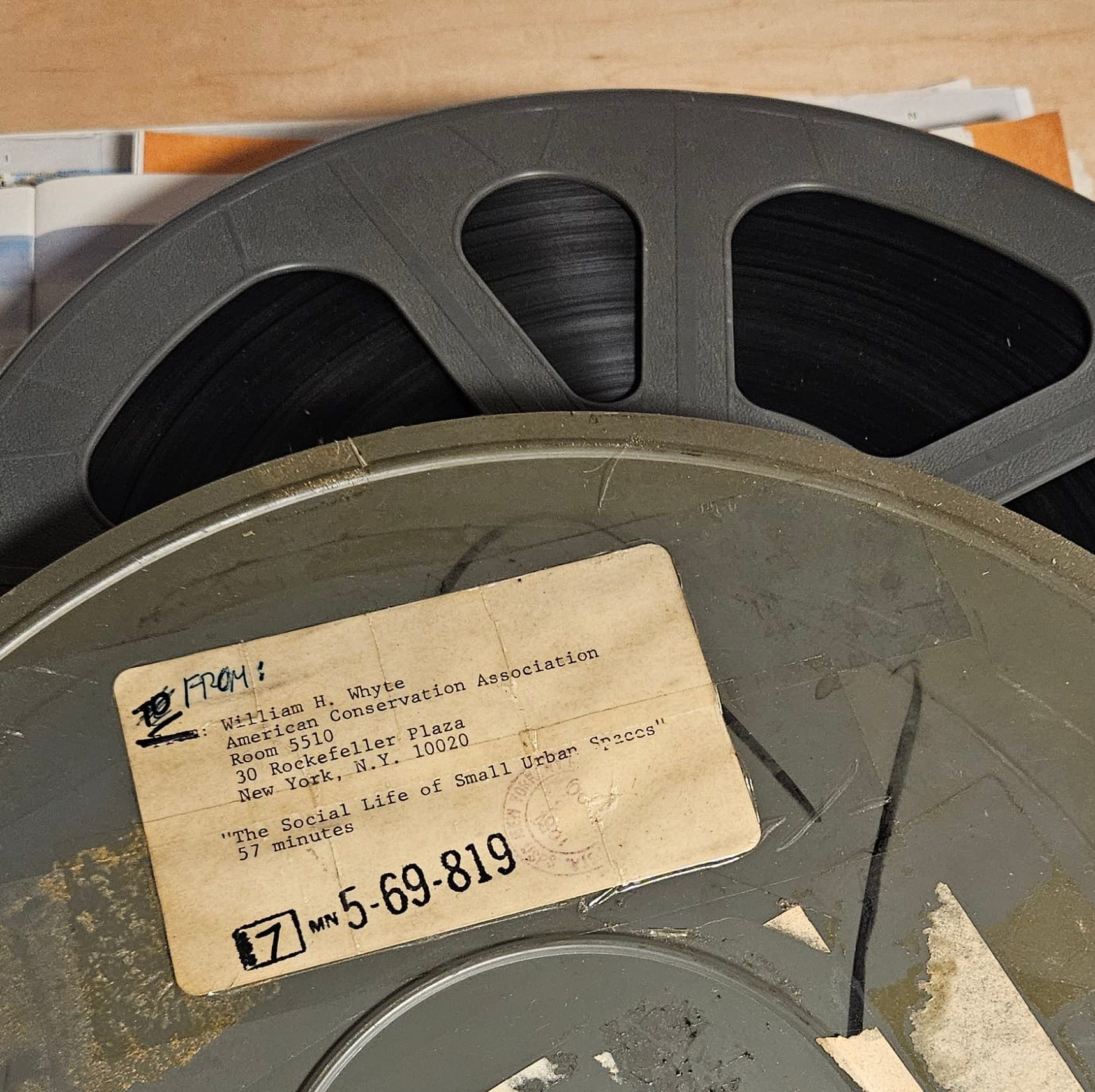

Holly came into studying cities in a roundabout way. Once the editor of Fortune Magazine, Holly is equally well known for his seminal book, The Organization Man (1956), which argued that American values of individualism and self-reliance were being replaced in the 1950s by a "groupthink" that prioritized the group over the individual. This trend was happening most visibly in the new suburbs of American cities, where houses were being built by the millions. Alarmed, and with the support of the American Conservation Association, he became intensely interested in the conservation of rural landscapes being destroyed by suburbanization (The Last Landscape, 1984) and later began to study the root causes of this trend. Was it because cities were thought to be so overcrowded that people had to spread out? That's one of the key reasons he started the Street Life Project a few years later. (Spoiler alert: It turns out that people liked crowded cities!)

"The social life of small urban spaces is not found by the planners, it is found by the people who use them."

The results of Holly's decade of work were the powerful film and book released in 1980 and entitled The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. The film and book are brilliant examples of Holly at his best: accessible ideas, persuasive data, great visuals, and humor throughout! Holly’s film was an enormous success, and people we meet remember it vividly decades after seeing it. Sadly, the version of the film that was in distribution for a long time was a very grainy print. That's why we are thrilled that the original film has been recently restored by Anthology Film Archives in New York City to a high quality edition, based on a 16mm print that we had kept in storage for decades!

In the book, he writes, “In 1970, I formed a small research group, The Street Life Project, and began looking at city spaces. At that time, direct observation had long been for the study of people in far-off lands. It had not been used to any great extent in the U.S. city.” The direct observation methods were simple: activity mapping of how people used a public space; counting the number of people; and using time-lapse filming to study overall usage patterns. Documentary film was also taken to present the results of the research that no bar chart could capture.

Documentary segments from the film explain research findings.

When Project for Public Spaces was created in 1975, Holly became an advisor. Inspired and trained by him, film was at the core of everything we did in the early years of the organization. We used Super 8mm film for analysis and to make our presentations. For presentations, we produced silent 10-15 minute presentation films that would play on our portable Super 8mm projector while we presented our findings. (Narrating a silent movie–with no pauses for side comments–really keeps you on your toes!)

Meanwhile, Holly was in his Rockefeller Center or Upper East Side office, finishing the film. He was always adding this and that, like footage from Los Angeles after a trip there. We often compared notes, and some of our research findings about specific spaces ended up in the film or book. We attended many of his popular "preview" presentations, where he would try out the latest edited version of the film, narrating it verbally. This, by the way, was how he also often wrote his books: reading what he wrote out loud to see how it sounded was a key step in the editing process. In any case, it was a very iterative process, which led the film restorer to comment on how many splices were in the original film!

This writing process was also the secret behind the power of his timeless quotes, which show the combined skill of a top magazine editor and a keen urban observer:

- "It is difficult to design a space that will not attract people. What is remarkable is how often this has been accomplished."

- "If you want to seed a place with activity, put in food."

- "The human backside is a dimension architects seem to have forgotten."

- "If those spaces are unattractive, people will likely retreat from the city street, perhaps from the city itself."

"We end therefore in praise of small spaces." Holly Whyte’s conclusion to the book is guided by this simple thought. "The multiplier effect," he continued, "is tremendous. It is not just the number of people using them, but the larger number who pass by and enjoy them vicariously, or even the larger number who feel better about the city center for knowledge of them. For a city, such places are priceless, whatever the cost. They are built of a set of basics and they are right in front of our noses. If we will look."

We are still looking, thanks to Holly.

"One felicity leads to another."