Inspiration for great public places can come from anywhere. Most recently, we found it in the Morikami Japanese Gardens in Delray Beach, Florida. These 16-acre gardens celebrate a long-lasting connection between Japan and Florida. The serenity that can be found there is nurtured by how the amenities and design features reflect the organic shapes and natural flow of the lands. It is a demonstration of how really seeing and listening to the essence of a space allows us to make the best possible place there.

Morikami Japanese Gardens History

Throughout time, people have cultivated gardens as reminders of a paradisiacal way of being. Some people grow flowers, others grow herbs on a windowsill, and still others create complex gardens meant for contemplation and appreciation of nature. Morikami's Japanese Gardens is one such example.

In the early 1900s, the Yamato Colony was established in Boca Raton by a group of young Japanese settlers who introduced their farming practices to the region. While most of them returned to Japan a few decades later, one George Sukeji Morikami stayed and later donated his lands to Palm Beach County. This became the Morikami gardens which now aims to share Japanese culture and traditions with Floridians and visitors from around the world.

Japanese Culture's Connection with Nature

Morikami Garden embodies the idea that “a garden is always a gift to those who come after us,” expressed by Ukrainian philosopher and theologian Oleksandr Filonenko. Morikami himself did not plant the garden, but he gifted the land to the county on the condition that it be used to preserve the memory of Japanese culture and to create a space of peace and contemplation. That is how the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens (Roji-en) came into being.

Japan has one of the highest population densities on earth, yet almost 70% of its total area is covered in forest. This coexistence with the natural landscape has led them to interpret nature's role in their lives in a unique way. They understand that much of human evolution occurred in the natural world and that it is therefore programmed into us, making it essential for us to return to nature in order to find peace, happiness, and wellbeing.

Recently, shinrin-yoku or "forest bathing" has become popular among the Japanese. This is the practice of going into nature to relax, recharge, and re-energize so as to heal from the stresses caused by the man-made world. Shinrin-yoku can be practiced by mindfully strolling through the woods, smelling the wood, soil, and flowers, stargazing, meditating in or close to sources of water, and other such peaceful practices in the forest. Gardens like Morikami's provide a lovely alternative environment where shinrin-yoku can also be practiced.

“The garden is the place where human time and natural time meet.”

— Robert Pogue Harrison

What the Morikami Gardens Can Teach us About Placemaking

What's so wonderful about these gardens is the way they don't fight with the landscape but organically weave through and enhance it. Human intervention here is meant to highlight the existing nature rather than force it into new shapes and directions that disconnect it from its original state. The gardens are an ode to how people and nature can coexist harmoniously and help each other thrive in resonance with themselves.

This is a great way to approach placemaking as well – highlighting the features that already exist in a particular place allows it to become "the best version of itself" – a beloved destination that retains its identity and honors its roots.

For example, if a park has a gnarled old tree, putting a swing on its branches makes it a focal point and anchor of the space. If there is a lake or lagoon there, a walking path set up around it following its contours, perhaps with interspersed benches, invites strolling and relaxing while appreciating a beautiful view. Boulders can become climbing spots, fields can be turned into event spaces or sports venues. In every natural feature of a space lies an opportunity for activation.

“In gardens we humanize nature and, at the same time, return ourselves to our own naturalness.”

Designing for Calm

Hoichi Kurisu, the Master Garden Designer said, “My hope is that visitors will allow the gardens to speak to them in the language of timeless truths and rhythms that can bring healing insights for the present. I hope visitors will listen, cherish, and act upon the inspiration that the gardens impart to each individual.”

Kurisu succeeded in realizing his vision. In Morikami Gardens, every place offers a sense of calm and life beyond time. The garden is designed to include numerous places for stopping and contemplation — points where movement turns into stillness.

Stone gardens called karesansui create inner silence — not because there is nothing there, but because there is nothing unnecessary. The focus is on the experience of being present.

The garden’s alleys intertwine with paths paved with fine gravel that softly rustles underfoot. And as soon as you step to the side, a forest awaits — with winding natural trails and wild thickets.

Bonsai trees are prominent in this garden. Bonsai is the art of growing miniature trees in containers. But these are not just small trees — they are great lives gathered into silence, places for contemplation. Within this system, bonsai becomes a center of inner focus. It teaches us that growth does not necessarily mean expansion; sometimes growth is the consent to remain within limits.

Waterfalls release tension, streams restore rhythm, and lakes teach silence. Water in this garden tunes one to a life without haste.

This is a space where architecture does not oppose nature, but breathes together with it.

Indeed, the Morikami Gardens evoke a paradisiacal way of being. Here, the sense of time dissolves, and the eternal emerges — people and nature together again, without fear or haste.

Olena Pikshrienie - Author

A Ukrainian author and visual storyteller who arrived in the United States in 2022 through the Uniting for Ukraine program. She holds a degree in philology and works with language, space, and video as ways of reflecting on experience and memory. She studies placemaking and views it as a tool for the postwar recovery of Ukrainian cities and communities.

My research resonates with the ideas of Ukrainian theologian and philosopher Oleksandr Filonenko, who speaks of rebuilding Ukraine as the cultivation of gardens — not as a rapid restoration of what was destroyed, but as a long, attentive process, rooted in care for the land, growth, and development. Gardens require time, patience, and love — just like a country learning how to live after war.

It is no coincidence that today the ideas of the American philosopher and Stanford University professor Robert Pogue Harrison, a supporter of Ukraine, find such a strong resonance in the Ukrainian context. His book “Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition” is a conversation about a world that can be rebuilt only through care, not through ruins.

Reconstruction begins where care appears — for people, for space, and for the meaning of life, not merely for the restoration of walls.

Who we are

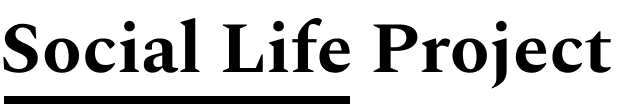

We are part of a growing group of community activists who have spent over 50 years building a "Placemaking Movement" globally that is now in over 30 countries around the world.

PlacemakingX/Social Life Project Team

If you are interested in collaborating (articles, presentations, exhibits, projects, and more) or supporting the cause contact us.