“The street is the river of life, the place where we come together, the pathway to the center.” —William “Holly” Whyte

Our streets are the greatest obstacle, and greatest opportunity, for changing our cities, and for changing how humanity thrives, and survives out of our current health, equity, and economic crises. Streets that are actively shaped, and loved, by their communities, sustain local economic inclusion, anchor social life, define culture. Such streets are a fundamental building block of civilization and driver of prosperity. But around the world this building block is weak.

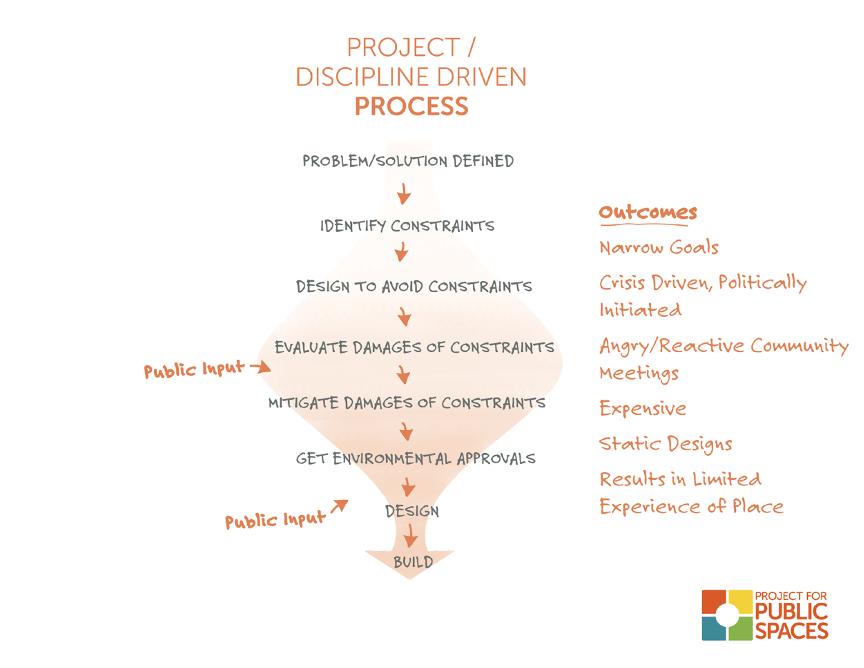

Unfortunately, for decades, the ability of communities to shape streets has been dominated by the separate and narrow goals and solution sets of usually one profession, whether transportation engineers, planners, architects, developers, car companies, or more recently smart cities technology. Understanding and supporting streets as places, places of shared purpose and meaning, has generally not been a focus of transportation planning and city building. Unfortunately, the often 20-30% of the land, and 50-90% public space, in our communities remains space to move through rather than to - missing many opportunities for these most connected spaces to drive value for, and shape, communities, and efficient transportation systems.

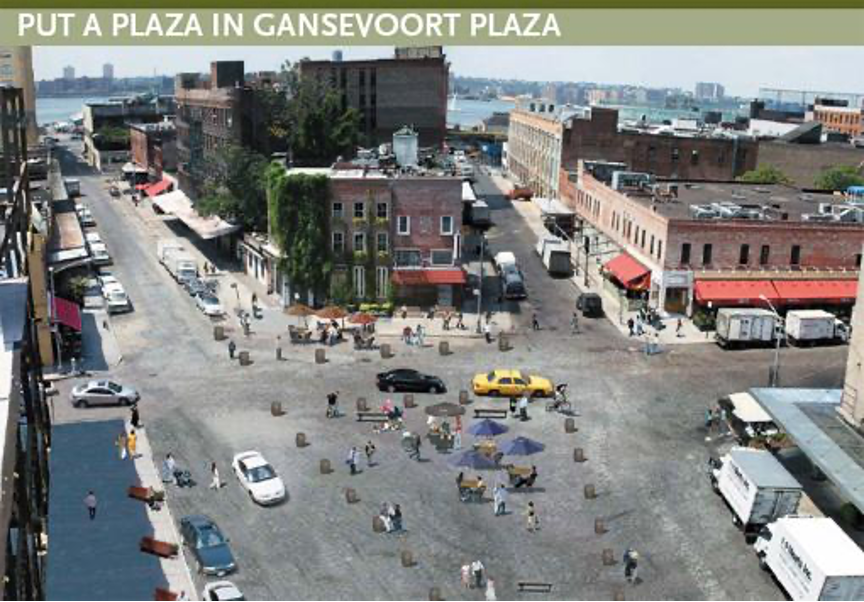

Streets, especially when planned similarly to roads, are often a detriment to the very destinations they are meant to connect. Because engineers have seen them principally as conduits for improved vehicle throughput, most of our streets are economically stifled, culturally generic, and socially isolating. Most seriously, using streets only as means to move more vehicles, more quickly, has caused an epidemic of violence inflicted on pedestrians, bicyclists, and motorists.

“Whatever a traffic engineer says, do the opposite and you’ll be building your community.” —Fred Kent in the 80s and 90s.

Our underperforming streets, and the narrow process through which they are often shaped, are limiting factors for thriving cities. Current roadway planning and design tend to be at odds with fundamental functions of cities to support safety, livelihoods, and human exchange and connection. Roads underlie our failure to address the global challenges articulated by the New Urban Agenda, like those of resilience, equity, and improving public health through better public spaces and pedestrian experience.

Since Fred Kent took this picture of eight ladies having to clutch each other to cross George Street in Sydney, the city has finally transformed the street from a divider to a connector.

To change this, we need to continue to evolve the framework for shaping our streets and cities. Much positive global momentum for better street design is building, as reflected in publications like Global Street Design Guide, and Street Fight: Handbook for an Urban Revolution. While offering a much improved, more balanced, place-sensitive solution set, these guidebooks, as any new solution, also threaten to perpetuate the same siloed, discipline-driven paradigm, unless couched within a larger place-led vision for change.

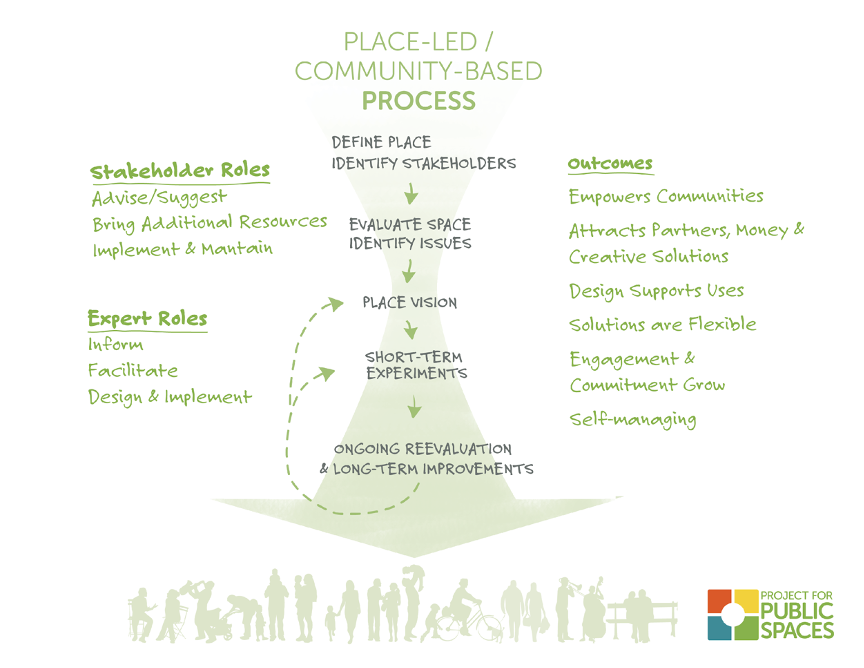

In making change sustainable, and able to address a community’s challenges, with a broad set of appropriate solutions, the process of public space planning, creation, and management needs to be centered in communities – a more “Jane Jacobs” process than the authors of Street Fight were willing to concede – and in fact argue against.

In order to support a true revolution in transportation planning, and sustain and demand, progressive transportation solutions, street transformation campaigns need to be community-based and focused on place and accessibility, as well as health, equity, and prosperity, as primary outcomes.

Citizens, and community-based organizations – not only elected officials and engineers -- effectuate change for their streets. Bold city-level leadership, and bureaucratic and technical proficiency are, of course, essential. But their work should be responsive to, and actually engage, inform, and inspire, grassroots action. In this dynamic, the transportation professionals become facilitators. They seed, and shape the discussion, and serve as resources for the process of creating streets for people, rather than the sole drivers of them. The best way to create cities for people is to create cities with people.

“Engineers should not design streets.” —Chuck Marohn, Traffic Engineer, Strong Towns

We certainly need more of the kind of progressive professionals now being attracted into the professions, and the solutions they are ably, and boldly, applying. The myth that change starts and ends with enlightened traffic engineers, is unfortunately limiting their impact and demand.

The process for transforming streets and public spaces can clearly start from any sector. In fact, we have observed that multi-sector collaboration actually leads to the boldest, most sustained, and effective changes in transportation policy. Key to such success is employing transportation professionals in the appropriate context: one that maximizes the added value of their expertise.

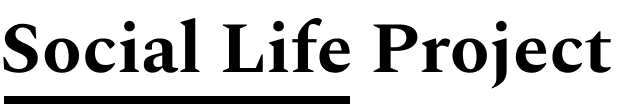

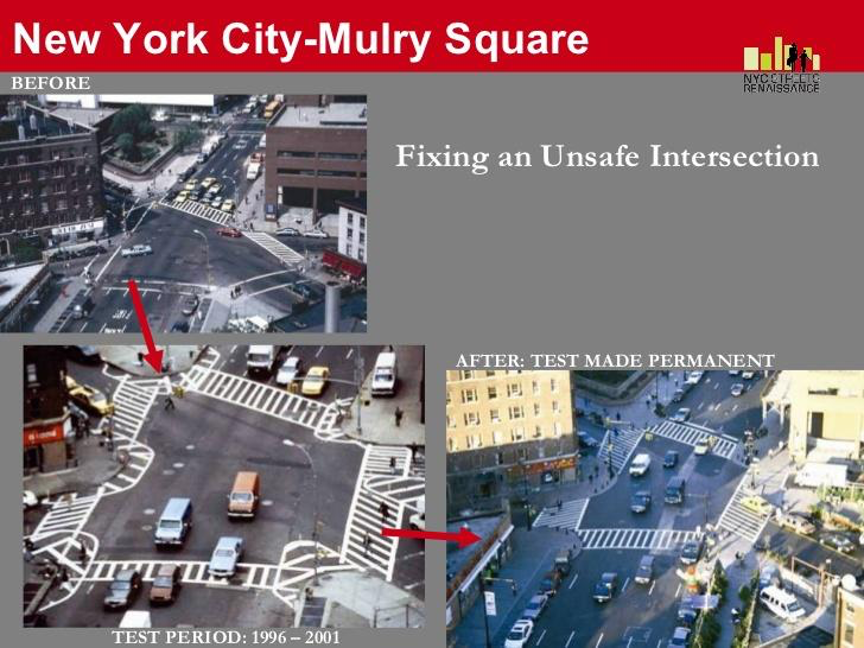

In fact, much of the change in NYC that the Bloomberg administration helped make happen, grew out of, and has been tirelessly sustained by, communities, local business groups, and advocates. Many of the “Street Fights” profiled – from the Meat Packing District, to the Prospect Park West Bike Lane, to Astor Place, to Times Square -- actually came out of such a place-led process, envisioned, defended, and sustained by local stakeholders and community advocates. In the most successful public plazas, it is the communities that partnered to create these plazas, that have defined, managed, and continued to improve these public spaces. The significant revolution in New York City was that after years of resisting advocates and community-based demands for change, the NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) finally began to allow, facilitate, and efficiently implement, the community’s ideas.

In NYC, the soil was tilled for revolutionary change from long-time grassroots, city-wide, advocacy efforts coalesced by the NYC Streets Renaissance Campaign. This was developed in 2005 by Mark Gorton and his Open Planning Project, in collaboration with Project for Public Spaces (PPS) and Transportation Alternatives. It launched publicly in January 2006 with a PPS directed exhibit at the Municipal Arts Society. In the couple years after, we helped organize and design similarly successful Streets As Places campaigns in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Antonio, Seattle, Philadelphia, and Adelaide, Australia.

NYC’s campaign was particularly successful because it achieved its aim of getting the campaign’s vision included in the Mayor Bloomberg’s PlaNYC encouraging a transition away from an unsympathetic Transportation Commissioner, and then quickly finding an ally in the Transportation Commissioner hired to replace her, and implement that plan, Janette Sadik-Khan. Janette has been an unparalleled leader in getting change to happen quickly for streets as public spaces, and inspiring change around the world. We need much more of her, and people like her shaping cities. We also now need to envision, and create, transportation systems where even bolder urban change can also draw leadership and resources from other departments and sectors.

We must remain wary of an approach that relies too heavily on small, design-led skirmishes only seeking reclamations of underused road space. While the goals are laudable, they threaten to perpetuate the process that got us into the problem to begin with - myths that traffic engineers, and strong leaders, can and should handle this alone, that advocacy leaders just organize the unruly, citizens just vote, and traffic engineering should focus, unimpeded, and in isolation, on ordering chaos to move various modes of traffic. We can evolve past the myth that everything is a fight between two sides, to participate in a more collective process to optimize the use of our streets and our transportation systems.

“There's just no place for a street fighting man.” —Mick Jagger

The focus on data-driven government has also been a means of perpetuating the top-down approach that distances, or buffers, government from dealing with communities. Project for Public Spaces pioneered, and advocated for data-driven public space user analysis and planning in NYC since the 70s, and PPS founder Fred Kent(my father) previously worked on such advocacy with William Whyte’s Street Life Project, and co-founding Transportation Alternatives. But in doing this analysis of spaces we came to the realization that our data, and expertise on a particular public space, was less valuable without inclusion of knowledge, perceptions, and feelings, of the actual users of the public spaces.

In the 90s, PPS developed placemaking as an approach to effectively include and empower communities, with processes and tools for constructive participation and place governance. These approaches aim to balance the quantitative analysis and communication, with the qualitative and emotional process that draws out community expertise, and action, and builds capacity and support for change. It is the perceptions and feelings of public space users, their emotional connections to streets, and how they create the social life of streets on a daily basis that ultimately determines a street's success.

Lovability of streets and public spaces may be a better focus than livability, which as a narrow goal often correlates with cost of living, inequality, and negative gentrification. Respecting, and facilitating, lovability of places, or place attachment (even if from “NIMBYs”), can more affordably, expediently, and inclusively achieve livability.

As PPS engaged communities in the Placemaking process, it also began to promote more short-term, low-cost, often local and informal uses, and management, of public space. In 2010 we started calling this strategy “Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper”, and saw how it could build momentum for further public space improvement and stakeholder engagement.

New York City began to seriously move towards a more community-led approach to public space improvement when it launched its Plaza Program, and related public space programs. The evolution here was to have communities apply with ideas for public space improvements, and required that community organizations be partners in their development. This process, and the plaza program, was first conceived, applied, and initiated under transportation commissioner Iris Weinshall, and then was more fully developed when Janette Sadik-Khan hired PPS’s transportation director Andy Wiley-Schwartz to run the program with subsequent hiring of many additional former PPS staff and advocacy partners.

The false narrative that public plazas and bike lanes were unilaterally introduced, entirely defensible by data, and resolutely pushed through by the transportation commissioner, is what created the backlash, often threatened the success, and is causing similarly narrow applications, and subsequent backlashes, globally. Of course the backlash, or “bikelash”, in NYC, also thanks to advocates led to a “backlash to the backlash”, as advocate journalist Aaron Naparstek wrote about in his “Street Fight” article, coining both terms.

The top-down process that led to streets tuned primarily for vehicles continues to perpetuate the divisive “street fight” dynamic in many communities, even when the problems and solutions are more holistically defined. We need city-wide campaigns to evolve the multi-sector collaborative culture of how communities, advocates, disciplines, and government collectively shape streets. Reinventing a more collaborative relationship between advocates, communities, and the city, was what the NYC Streets Renaissance Campaign modeled with numerous public events, a dozen community-based demonstration projects, and the launch of Streetfilms and Streetsblog.

We all now need to clearly articulate how to build on the successes we have had from traffic engineer led-change in NYC, and beyond, and to work to expand these achievements nationally and globally, and take it to a new level. Let's lay out a vision that ideally circumvents, or at least benefits from, street fights and accomplishes much larger wins -- specifically the capacity of communities to define, and sustain, thriving streets.

All around the world, the idea that streets should be devoted to fast moving vehicles, and along with it parking, took over like a virus, leading to the privatization of our public realm with dangerous machines. We need a new paradigm for cities and governance. We need to build communities through transportation not transportation through communities. Placemaking can start lighter, quicker, and cheaper actions to rightsize streets, as a catalyst to getting communities to build their capacity to be effective partners in change.

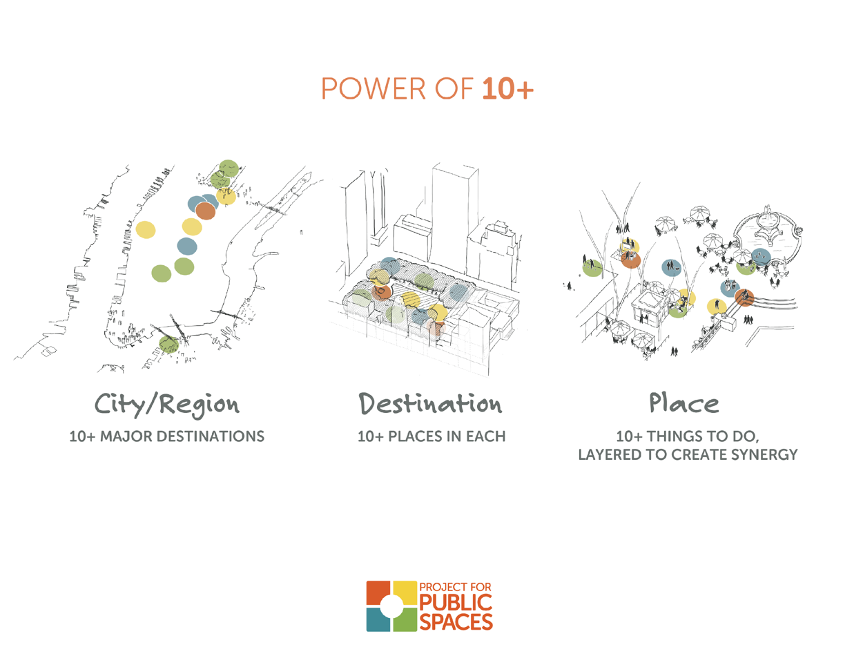

NYC’s metamorphosis, and those of many other cities, has been led by the transformation of great public spaces. While city government has often played a key role in making these happen, the most notable public space transformations started with community-based advocacy. The community-based organizations that emerged from these processes of improving streets and public spaces - often created to challenge city policy, or the activities of private developers - are now sustaining the most successful public spaces, defending them, and helping them thrive.

The same way the departments of transportation were focused on unimpeded mobility for vehicles, government and place-led governance can evolve to facilitate the highest and best use for streets as defined by their communities. In much the same way unimpeded car culture was sold to us as convenient, sexy, and “high class”, streets as places for people can be sold, and go viral.

But great streets aren’t just something you consume as aesthetic or functional, great streets are where everyone, from the store owner, to the pedestrian, to the designers, are competing to contribute to shared value in the public realm - to the public life and the civic commons. This ongoing focus on creating streets as places creates a virtuous cycle of placemaking that reverses the ponzi scheme of transportation and land use planning of the last 70 years – where every participant has been set up to the degrade shared value of the public realm. The narrow focus on mobility usually overlooks place, causing us to move around more and more, while often accomplishing less and less – perpetuating the disconnection that underlies so many of society’s challenges.

Using the Prospect of Autonomous Cars to Catalyze Streets As Places

Let’s turn upside down our transportation system, and the process through which it is created, to start with places.

While we need to make people, places, and cities more autonomous from vehicles, being against cars will not get us there. And autonomous cars may actually be our big opportunity. The conversation and potential of autonomous vehicles allows for the perfect opportunity to rethink and redesign transportation systems. AVs can thrive, and outcompete their less safe predecessors, in a transportation system defined around pedestrian rich destinations. Autonomous vehicles will need destinations to go to, but will, and should, have difficulty getting through pedestrian rich areas.

A transportation revolution that focuses on creating great places can ultimately create a transportation system that is more compatible with car sharing and self-driving cars. Electric vehicle charging stations can also be either planned to support active public destinations or further privatize public space with large automobiles.

Successful campaigns for change start with small, temporary demonstration projects, where communities are ready to lead change, then build toward, and start to sell, a bold vision for systemic change and capacity building for broader transformation of streets.

Many of these demonstrations can be defined around public destinations, and destination streets. Arterials should still carry significant throughput, but can benefit from much less cross traffic, and narrower intersections. Every neighborhood should have destination streets that support local retail that drives very busy sidewalks, causing further friction and slowing traffic. Residential streets, if desired by neighbors, should be allowed to become destination streets with very slow speeds and priority for people spaces over parking spaces.

It would no longer be a street fight of incrementalism and anguish, but an exponential evolution of streets, and the capacity to transform them. It would happen organically and not require high investment of political and financial capital. To really be able to shape cities to serve communities and address our larger societal challenges we shouldn’t wait for enlightened bureaucrats to incrementally change the design of streets.

Great streets, and great changes, require broad participation and support. Defining the problem and solution around transportation, or the tools of one discipline will continue to limit, and degrade, the potential for change. To truly complete our streets, and our communities, we need to ramp onto the bigger idea of Streets as Places. Street design is even more important than is understood, but not the limiting factor for transforming streets. Great streets start, and end, with the life of communities. Let’s go to the next level to create great streets that really draw out the life of the communities they are meant to serve.

This article is part of The Social Life Project's focus on shaping streets and sidewalks for, and from, social life. Originally written in 2016, this is the first time this article has been published publicly.

Related Articles

Further Reading